There's a moment, somewhere around kilometre 95, when you realise you're almost home. Not home to your temporary apartment, but home to the beginning of a line you drew through a city without asking permission. Home to the arbitrary point where you decided to start mapping a place that already had perfectly good maps, thank you very much.

But this wasn't about good maps. This was about meandering as method.

Following the Aesthetics

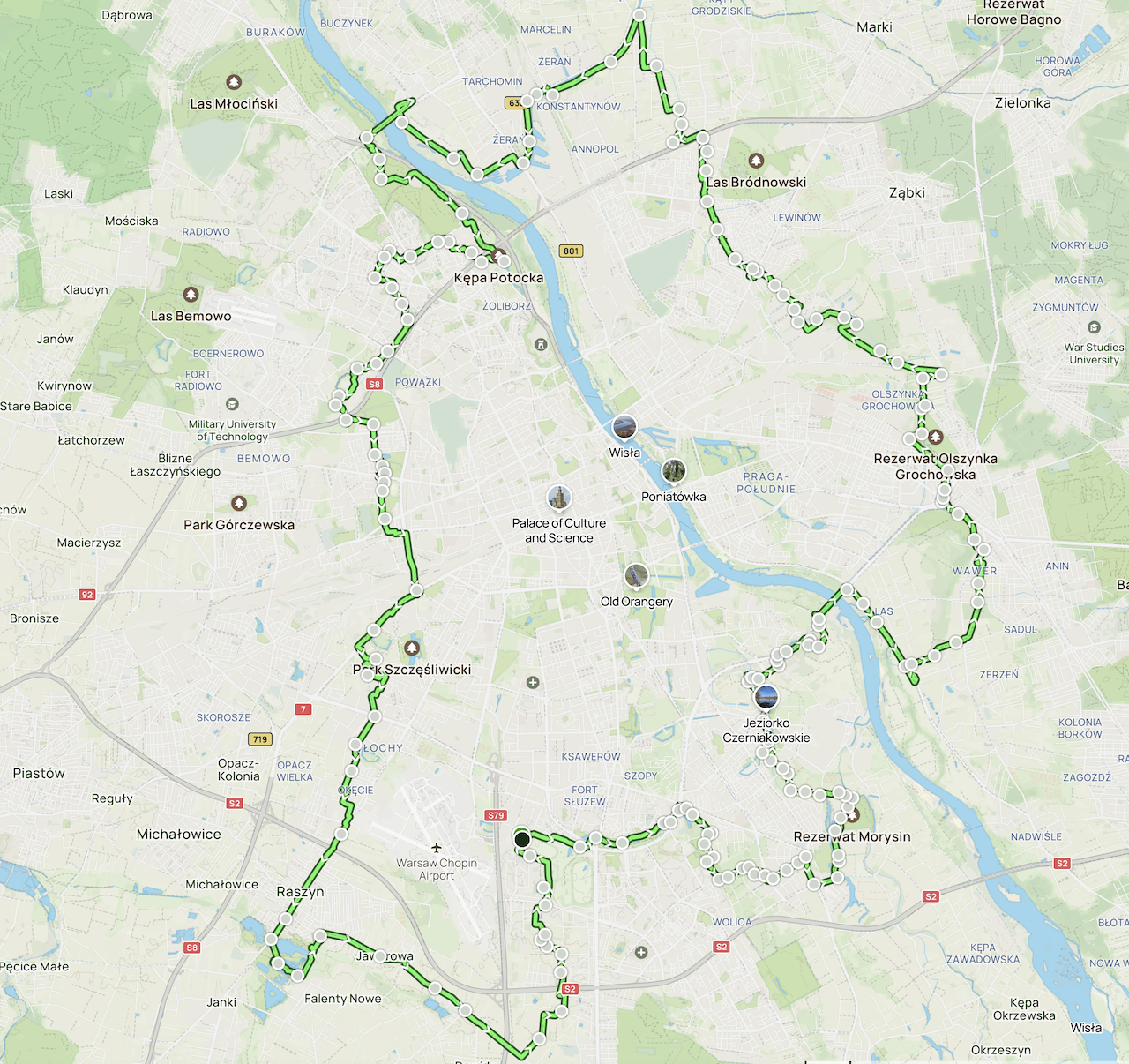

It began with a canal - Kanał Bródnowski, if you must know, though names feel inadequate for what I was really following. I was chasing something more elusive: the aesthetics of the everyday, the quiet poetry that lives in the spaces between monuments. What started as an afternoon walk stretched into something larger, something that demanded completion. By the time I looked up from my intuitive wandering, I had traced the skeleton of a circle around Warsaw.

All 108 kilometres of it.

The postmodern condition teaches us that all maps are fictions, that every representation is a construction. But what happens when you construct your own fiction?

When you decide to know a city not through its official story but through your own process of discovery? You become both cartographer and territory, both the one who walks and the path itself.

Each afternoon, I would take the bus to yesterday's endpoint and begin again. This ritual of return became as important as the walking itself - these liminal moments of transition, watching familiar neighbourhoods slide past windows while carrying the memory of how they looked at ground level, step by step. The city revealed itself in layers: the version seen from bus and tram seats, the version walked at human pace, the version that emerged only after hours of accumulated quiet observations.

Meandering, I discovered, is not aimless wandering but a methodology unto itself. It's the practice of letting aesthetics lead, of following the pull of light down an unexpected street, of trusting that beauty knows something about truth that efficiency has forgotten. My route emerged not from any logic an urban planner would recognise, but from the accumulated decisions of choosing the more interesting path, the one that felt more alive.

Here's a thing - the Dadaists called it dérive - the practice of drifting through urban landscapes, allowing the city's psycho-geography to guide movement rather than purpose or destination. But dérive was meant to be more disruptive, a way of challenging the rational order of modern cities. My circular route became something different: not a rejection of order but the creation of a new kind of sense, a personal mythology written in footsteps.

What I found in those 108 kilometres (not including countless dead ends) was the Warsaw that exists in the margins of guidebooks. The elderly woman who tends a garden that no city planner officially knows about, coaxing flowers from a patch of earth beside a concrete wall. The teenagers who have transformed a forgotten underpass into an informal art gallery, their graffiti more honest than anything hanging in the museums downtown. The morning commuters at bus stops who carry themselves with a particular kind of dignity, dressed for work but somehow untouchable by the mundane weight of routine.

The Quiet Landmarks

These quiet places became my landmarks. Not monuments to kings or battles, but monuments to the ongoing act of living. The corner where bread smells drift from a bakery window at precisely 3.23PM. The stretch of path where the light falls just right at evening, turning ordinary concrete into something that resembles amber. The bench where someone has carved initials with such careful precision that it becomes a meditation on love as temporary permanence.

Walking this route, I also began to understand something about circles that I hadn't considered before. A circle has no beginning and no end, which means every point is both. Each day's walk was simultaneously a completion and a beginning, a return and a departure. The route became a kind of ritual circumambulation around a city that was teaching me as much about myself as about its own hidden geographies.

The postmodern insight is that identity - of places, of people - is always constructed, always provisional. But construction doesn't mean fake. It means chosen. My Warsaw, the one I walked into existence over three months of patient observation, is as real as any other Warsaw. More real, perhaps, because it was earned through attention rather than inherited through tourism.

There's something almost monastic about the discipline of walking the same expanding route day after day. The daily bus rides back to the beginning, the careful attention to where yesterday ended, the gradual accumulation of a personal map that exists nowhere except in memory and GPS traces. It reminded me of the Buddhist practice of walking meditation, where the act of moving becomes both the method and the destination.

But unlike meditation, which seeks to transcend the physical world, my walking was deeply embedded in materiality. The varying textures of pavement under foot, the way different neighbourhoods smell at different times of day, the accumulated knowledge of which streets flood slightly when it rains, which corners catch wind in unexpected ways. My body became an instrument of measurement, calibrated to the specific rhythms of this specific place.

The Paradox of Completion

As the circle neared completion, I found myself walking differently. There was something ceremonial about those final kilometres, a recognition that I was completing not just a route but a relationship.

The Warsaw I was finishing with was not the same Warsaw I had started with, and neither was I. The circle had changed us both.

The final morning, walking the last few kilometres back to the canal where it all began, I finally understood something about the nature of completion. Circles are paradoxical - they're closed systems that somehow contain infinite possibility. Every point on a circle is equidistant from the centre, which means every moment of the walk was equally central to the experience. There was no climax, no destination more important than any other.

Standing at the endpoint that was also the beginning point, I realised I had created something that couldn't be easily categorised. Not quite a tour, not quite a pilgrimage, not quite an art project. Perhaps it was simply what happens when you decide to know a place through sustained attention rather than casual observation. When you commit to understanding through accumulation rather than highlights.

The route exists now as a line on my maps, but also as something more elusive - a feeling, a frequency, a way of moving through urban space that prioritises discovery over destination. It's a methodology that could be applied anywhere, this practice of following aesthetics wherever they lead, of trusting that beauty has its own logic, its own geography.

I can share the coordinates, plot every turn and rest stop, provide the bus routes and distances that made it possible. The data exists, precise and reproducible. But here lies the beautiful paradox: anyone could theoretically follow my exact route, yet they would have completely different experiences. They wouldn't bring three months of accumulated observation, the gradual relationship built with each neighbourhood, the seasonal changes witnessed, the slowly calibrated understanding of how this particular city breathes. The map becomes both invitation and impossibility - I can share the coordinates but not the meaning I found there.

This is perhaps the most honest thing about maps: they can show you where to go, but never why it matters.

In a world of increasingly standardised urban experiences, where cities risk becoming interchangeable backdrops for the same chain stores and tourist attractions, meandering becomes a form of resistance. It's a way of insisting on the particular, the local, the irreducibly specific. It's a method for discovering the city that exists beneath the city, the one that reveals itself only to those willing to walk its full circumference.

Going full circle in Warsaw has taught me that knowledge isn't always about reaching a destination. Sometimes it's about creating a shape in space and time, tracing a line that completes itself, drawing a boundary that becomes, paradoxically, a way of touching the infinite.

The route is complete, but the walking continues. There are always more circles to be drawn, more cities waiting to be read step by step. The methodology remains: follow the aesthetics, trust the meandering, let the city teach you how to see it properly.

After all, the most important discoveries happen not when we arrive somewhere, but when we realise we've been somewhere all along.

Music: Zeran Winds by D. Henzell