"The past is a text, but it's a text that keeps rewriting itself."

Walking through the pine forests of Poland's Hel Peninsula the other day, I was struck by the sudden impossibility of my task. You see, I was trying to read a narrative that had no reliable narrator, no single author and no coherent plot. The woodland I was surrounded by felt eternal, peaceful enough - but I realised this feeling was itself just another layer of interpretation, another story I was telling myself about what nature really means.

Because, when I looked closer, the forest began to reveal its secrets. Or did it? Perhaps what I discovered said more about my own need to find meaning than about any inherent truth hidden in the landscape.

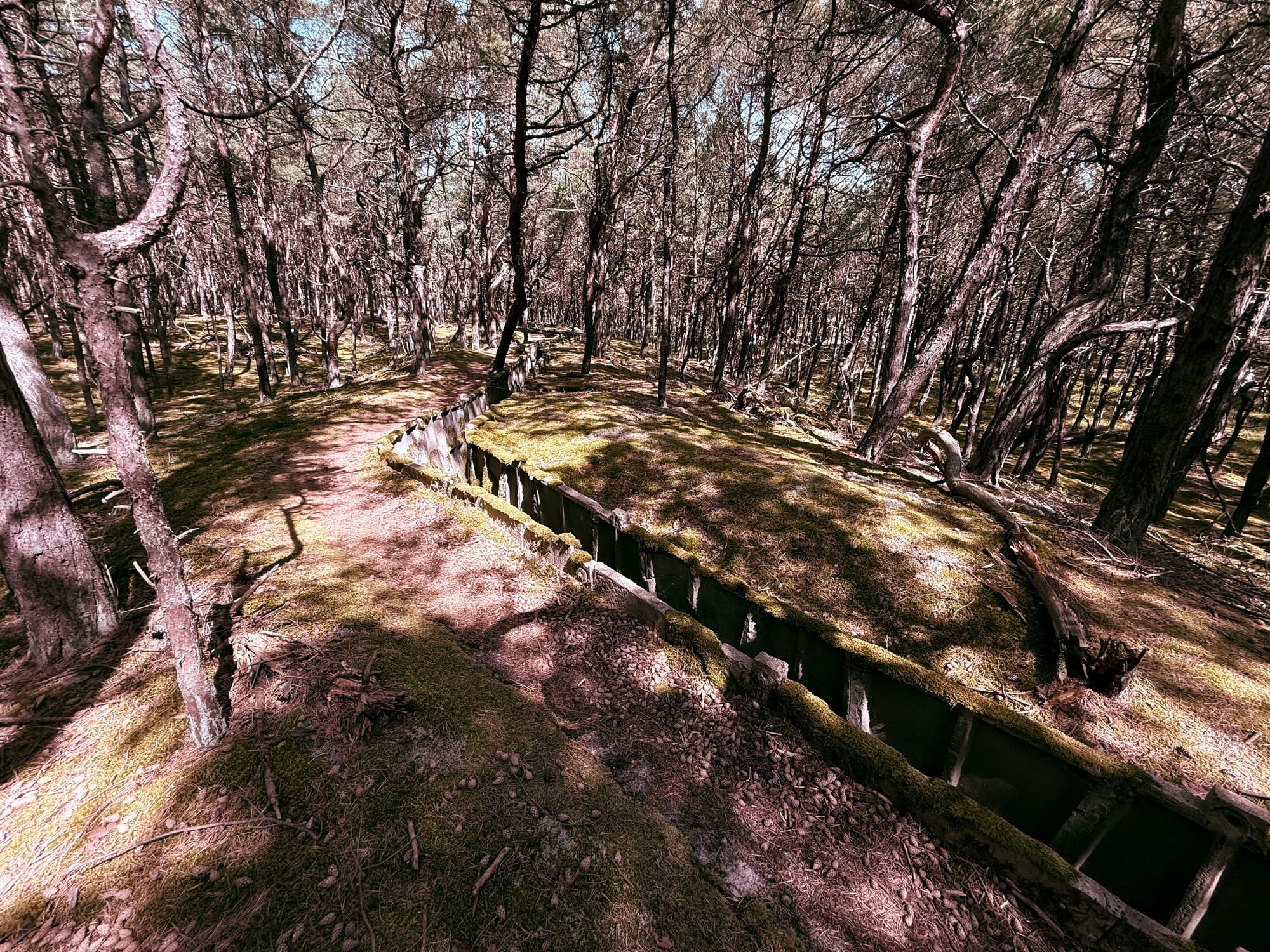

Hidden beneath decades of moss and emerging vegetation, concrete-lined trenches snaked through the trees like scars that refuse to heal. These scars are not natural formations but deliberate wounds carved into the earth by human hands driven by fear, strategy, and the relentless march of history.

The Impossibility of Historical Truth

What struck me most about these abandoned fortifications was not simply their physical presence, but the vertigo of trying to construct a coherent narrative from such unexpected fragments.

And here lies a very postmodern predicament: I encounter concrete-lined trenches and immediately begin weaving them into a story of "shifting allegiances" and "tumultuous history" - but this story is, I'd wager, as much a product of my contemporary imagination and perspective as it is about historical reality.

This hidden trench system represents not just different military strategies, but entirely different ways of understanding reality itself. The Polish engineers of the 1930s inhabited a universe where linear defence made sense, where concrete barriers could hold back the chaos of modern warfare. The Germans who modified these positions operated within a different epistemological framework - one that saw the Baltic as part of a vast continental empire. The Warsaw Pact forces who poured concrete into these trenches lived in yet another reality, where the threat was ideological contamination from the capitalist west.

But here's the unsettling truth: I have no access to what these trenches "really" meant to the people who built them. I can only encounter them through the filter of my own historical moment, my own assumptions about war, peace, and meaning. The "history" I'm constructing is really just another text, layered onto the landscape like digital graffiti.

The Simulation of Threat

Consider the absurdity: I'm walking through fortifications built to defend against enemies who never came, modified by occupiers who became the occupied, expanded by liberators who became oppressors, all now existing within an alliance system that would have been incomprehensible to any of the original builders. Each layer of construction represents a simulation of threat - not the threat itself, but a society's mediated understanding of what threat means.

My old pal Jean Baudrillard might recognise these trenches as pure simulacra: concrete manifestations of fears that existed primarily in the realm of strategic planning, war games, and political imagination. The "enemy" these fortifications defended against was always already a construction, a projection, a hyperreal threat that shaped material reality while remaining essentially fictional.

The Polish trenches defended against a German invasion that was both inevitable and unimaginable. The German modifications prepared for Allied landings that never came to this shore. The Warsaw Pact concrete anticipated NATO amphibious assaults that existed primarily in the pages of military doctrine. Each defensive system was responding not to actual threat but to the media of threat - intelligence reports, propaganda, strategic assessments that created the very reality they claimed to merely describe.

The Aestheticisation of Violence

Looking back, I realise there was something profoundly postmodern about my response to these fortifications. I found them beautiful. Not despite their military purpose, but because of how that purpose had been emptied out, commodified, transformed into an aesthetic experience for the heritage tourist. The concrete that once embodied lethal intent now served as a backdrop for my Whats App-worthy forest photography to share with friends.

And this, I suspect, is late capitalism's genius at work: transforming even the instruments of state violence into consumer experiences. These trenches have been unconsciously curated by time and neglect into something approaching land art. I then happily consumed their menace as atmosphere, their history as narrative, their decay as romantic melancholy. Maybe the forest hadn't reclaimed these fortifications after all - the culture industry had.

The "beauty" I perceived in moss-covered concrete revealed more about contemporary aesthetics than about any inherent quality of the fortifications themselves. I was viewing military infrastructure through the lens of ruin porn, apocalyptic chic, the same sensibility that finds bombed-out cities photogenic or sees Chernobyl as a tourist destination. The violence had been safely aestheticised, the threat domesticated into ambiance.

How long, I wonder, before the battlefields of Ukraine undergo the same transformation - their trenches and destroyed cities repackaged as heritage sites, their trauma commodified into dark tourism experiences for future visitors seeking authentic historical encounters? Visitors like me?

The Archaeology of Paranoia

Walking through those trenches, I found myself thinking about the archaeology of paranoia each layer represented. The concrete I touched had been poured by people living inside radically different media environments, consuming entirely different information ecosystems, inhabiting parallel universes of meaning.

For the Warsaw Pact engineers, the West had represented existential threat not because of any specific military capability, but because Western media, Western ideas, Western ways of life threatened the very foundation of socialist reality. The concrete they poured was defending not just against physical invasion but against semiotics - against signs and symbols that could unravel their entire worldview.

But thinking about it now, I recognise the recursive twist: my own interpretation of these trenches was equally conditioned by my contemporary media environment. I read these fortifications through the lens of postmodern theory, heritage tourism, and historical irony - interpretive frameworks that would have been as alien to the original builders as their ideological commitments were to me. I wasn't discovering the "true" meaning of these trenches; I was participating in the endless deferral of meaning that characterises postmodern textuality.

The End of Grand Narratives

Looking back now on my walk, I could see how they embodied Lyotard's insight about the end of grand narratives. Each successive military power that controlled this peninsula had believed they were defending civilisation itself - whether Polish independence, German Lebensraum, or socialist internationalism. Each had metaphorically poured concrete with absolute certainty about the righteousness of their cause and the clarity of the threat they faced.

Yet from my vantage point that day, all these grand narratives appeared equally contingent, equally constructed. The Polish nationalism that built the original fortifications, the German expansionism that modified them, the Soviet ideology that reinforced them - all revealed themselves as localised language games rather than universal truths. The concrete remains, but the meanings that justified its pouring has evaporated.

For me personally, this was perhaps the most unsettling aspect of encountering these fortifications: they forced me to confront the possibility that my own interpretive frameworks - democracy, human rights, historical progress - might appear equally arbitrary to some future archaeologist of ideology. The trenches I was walking through had been built by people as convinced of their worldview as I was of mine.

The Tourist of Ruins

Ultimately, I must acknowledge my own position in this palimpsest of power: I am the heritage tourist, the consumer of historical trauma, the postmodern flaneur strolling through landscapes of former violence now safely packaged as "historical interest." My very ability to find these trenches aesthetically compelling, intellectually stimulating, blog-worthy, depends on their complete disconnection from any actual threat.

I photograph moss-covered concrete for pleasure, I theorise about simulation and hyperreality, I construct postmodern narratives about the arbitrariness of historical meaning - all from the comfortable position of someone for whom these fortifications represent no danger whatsoever. This too is a form of violence: the violence of interpretation, the colonisation of trauma by theory, the transformation of genuine historical terror into cultural capital.

Indeed, the families playing on the beach less than 200 meters away have perhaps the most honest relationship to this landscape - they ignore its military history entirely, treating the peninsula as pure recreation space. They refuse the burden of historical meaning, the obligation to read significance into every concrete remnant. Perhaps they understand something I don't: that the most radical response to these accumulated layers of paranoia might be simple, wilfull forgetting?

Fragments Against Ruin

And so it goes. These trenches will continue to decay, their concrete gradually returning to the chemical elements from which it was formed. The interpretive frameworks I've used to understand them - postmodernism itself - will eventually seem as dated as the military doctrines they once embodied. Future visitors might read entirely different meanings into these ruins, or might not read them at all.

What remains is not truth but trace: the material fact of concrete and earth, shaped by human hands for purposes that no longer seem urgent or coherent. These fortifications have become texts without authors, signs without stable signifieds, monuments to the ultimate impossibility of permanent meaning in a world where everything solid melts into air.

Perhaps that's enough.

Perhaps the most profound thing these trenches can teach us is not about the past they were built to defend against, but about the future they never imagined: a world where their certainties have become incomprehensible, where their fears have transformed into tourist attractions, where their concrete permanence has become just another layer in time's endless palimpsest of forgetting and remembering and forgetting again.