"Time is not a line but a dimension, like the dimensions of space."

- Margaret Atwood

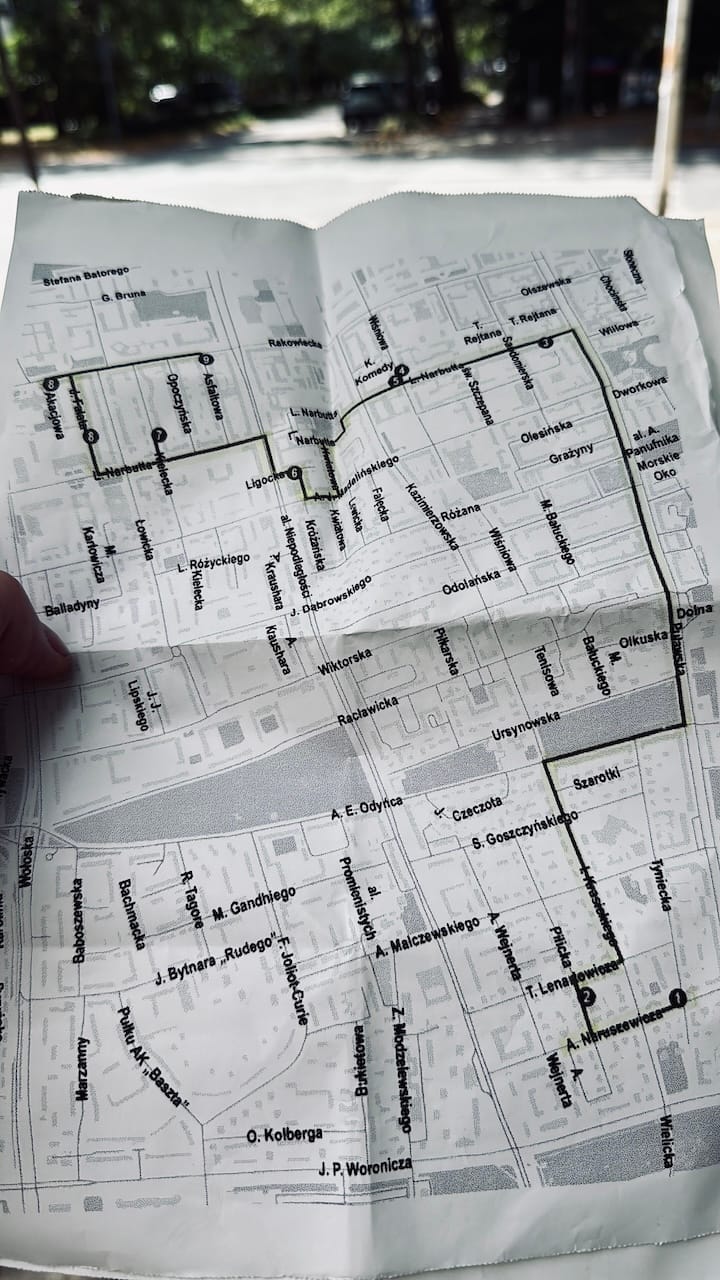

In the calming streets of Warsaw's Mokotów district, something extraordinary happens to time. It bends, fractures, and bleeds through the facades of century-old tenements where the bullet holes from 1944 refuse to heal. These punctures in brick and mortar are more than mere architectural scars - they are temporal wounds where the past violently erupts into the present, creating what I'm calling "temporal bleeding": moments when linear chronology collapses and multiple historical moments occupy the same physical space.

Walking through these streets on a late summer afternoon, I find myself not just discovering war damage, but capturing time itself in a state of rebellion against the forward march of progress. Each bullet hole becomes a portal where August 1944 bleeds through into August 2025, where the screams of the Warsaw Uprising echo beneath the hum of contemporary traffic, where the city's attempt at temporal healing is perpetually interrupted by material memory that refuses to fade.

Ul. Naruszewicza 10.

The Postmodern Condition of Memory

In our postmodern era, we've grown accustomed to the idea that history is constructed, that memory is malleable, that the past is always filtered through the present's needs and neuroses. My old mucker Jean Baudrillard warned us of the hyperreal - the simulation that precedes and ultimately replaces reality. Warsaw's painstakingly reconstructed Old Town, with its Disney-perfect medieval facades, epitomises this phenomenon. It is more "old" than the original ever was, a simulation so convincing that tourists photograph it believing they're capturing authentic history.

But in Mokotów, something different happens. Here, the bullet holes resist this postmodern flattening of time. They are stubbornly, violently real. They cannot be reconstructed, only preserved or erased. They represent the political unconscious of the city - the repressed trauma that surfaces despite narratives of renewal and progress.

These holes challenge our contemporary relationship with time itself. In our digital age, we experience temporality as increasingly fragmented - past, present, and future collapse into the eternal now of social media feeds and 24-hour news cycles. But Warsaw's war scars offer a different kind of temporal disruption: not the smooth, seamless blend of postmodern pastiche, but jagged interruptions where the past crashes through with uncompromising brutality.

Ul. Pilicka 18.

The Architecture of Temporal Wounds

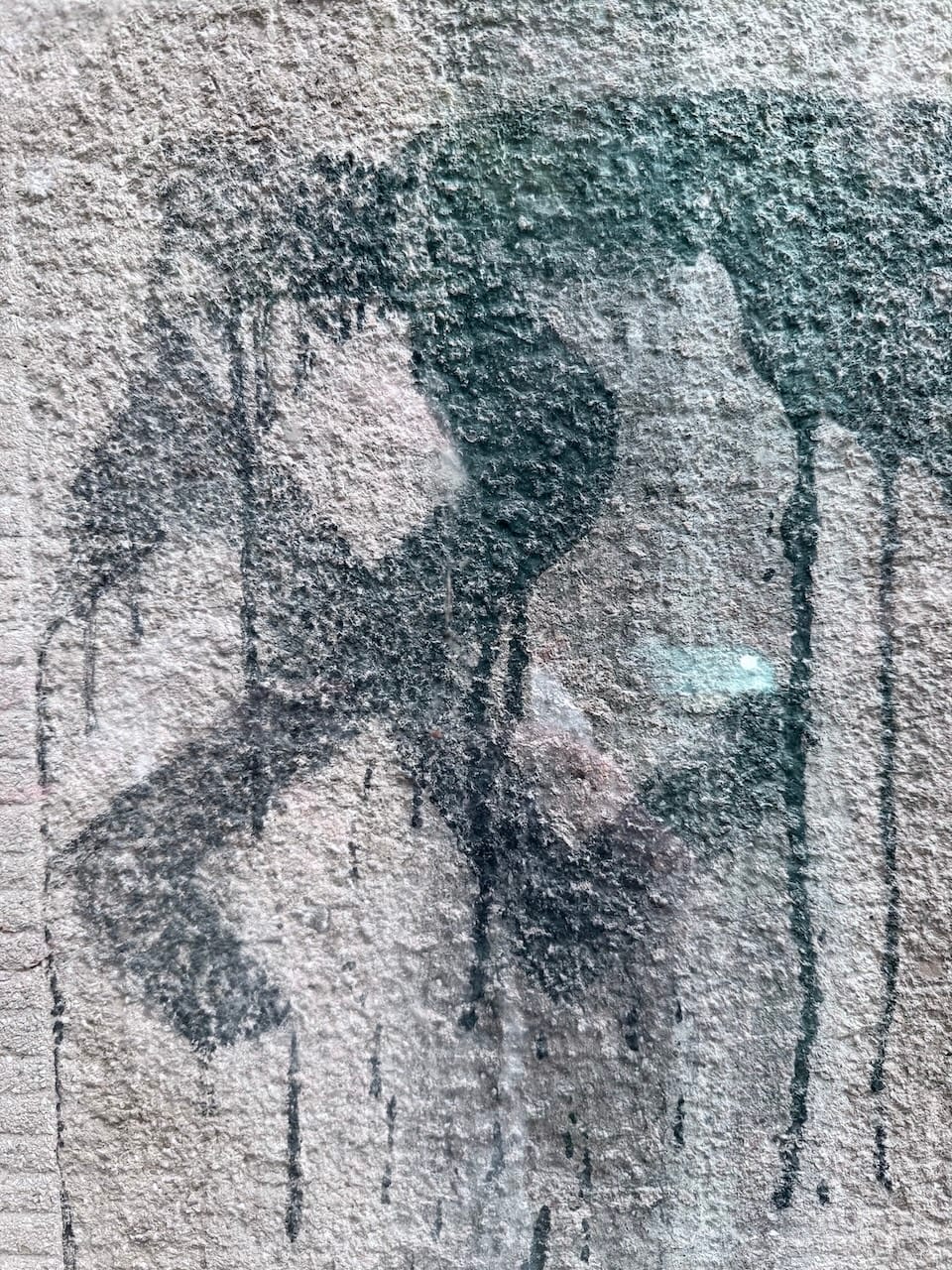

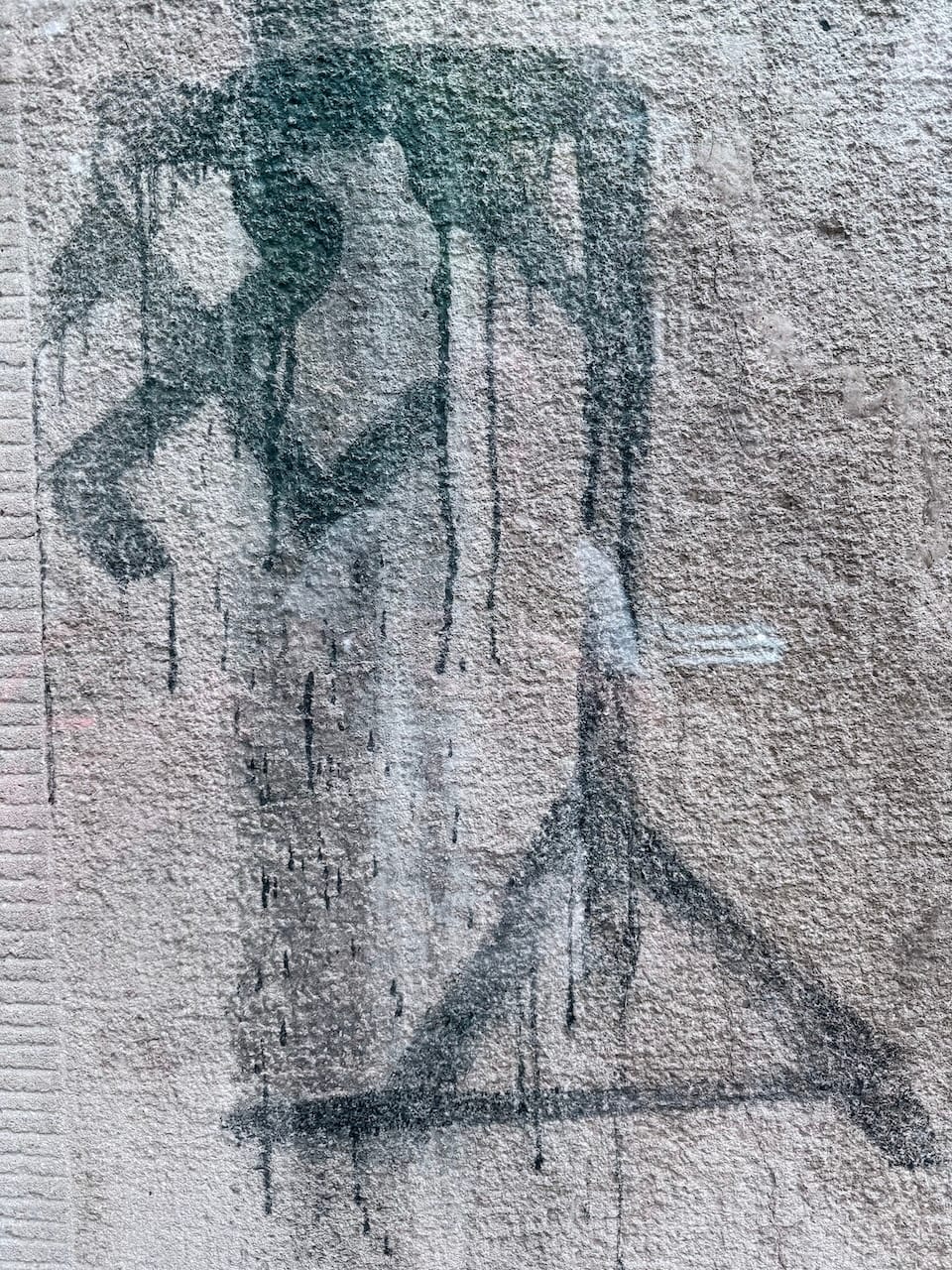

Each bullet hole is a miniature monument to the moment of its creation. Unlike traditional memorials, which translate trauma into symbolic language, these wounds speak the literal language of violence. The hole torn by a German machine gun in the facade of a Mokotów tenement carries within it the precise physics of that August morning in 1944: the trajectory of the bullet, the speed of impact, the resistance of nineteenth-century brick.

But what makes these holes particularly fascinating from a temporal perspective is their refusal to age gracefully. While the buildings around them have been painted, renovated, gentrified, and adapted to contemporary needs, the bullet holes remain frozen in their moment of creation. They are temporal islands, preserved accidents where time stops.

Consider for a moment the philosophical implications if you will: in a world obsessed with renewal, upgrade, and optimisation, these holes represent the persistence of the unrepairable. They cannot be improved, only destroyed or maintained. They exist in a kind of temporal limbo, neither fully past nor successfully integrated into the present.

Ul. Narbutta 30.

The Phenomenology of Temporal Bleeding

Standing before one particular bullet-scarred wall on Ul. Naruszewicza, I'm told photographers and visitors often report a strange sensation - a feeling that multiple time periods are somehow present simultaneously. This cannot be mere nostalgia or historical imagination. It's a genuine phenomenological experience where the material traces of past violence create what one might call an "embodied memory" that exceeds conscious recollection.

The camera becomes a crucial tool in this temporal archaeology. Photography, with its ability to freeze moments, has always had an ambiguous relationship with time. But when photographing these wounds, something unique occurs: the camera captures not just the present appearance of past damage, but the temporal bleeding itself - the way history refuses to stay buried.

On this walk, and with my images, I'm trying to capture this temporal confusion. A close-up of bullet holes in harsh afternoon light might show the precise shadows cast by their edges, shadows that change throughout the day just as they did in 1944. A wider shot might include contemporary elements - a parked car, a modern sign, a person walking by - that create jarring temporal juxtapositions. In such instances the past literally shares the frame with the present.

Ul. Wiśniowa.

The Politics of Temporal Preservation

The preservation of these wounds is never neutral. In post-communist Poland, decisions about which traces of the past to maintain and which to erase carry profound political implications. The bullet holes represent a specific narrative of Polish suffering and resistance, one that sits comfortably within contemporary national identity.

But this selectivity reveals the constructed nature of temporal bleeding. Some wounds are allowed to persist while others are carefully healed. The holes from German bullets during the Warsaw Uprising are preserved, while the damage from later Soviet occupation is often erased. The past that bleeds through is curated, edited, ideologically shaped.

This curation process exposes a fundamental postmodern paradox: even our most "authentic" historical traces are mediated by present concerns. The bullet holes persist not simply because they're too difficult to repair, but because they serve contemporary narratives about Polish heroism, German aggression, and the sanctity of resistance.

Yet their material presence exceeds these narratives. Stand close to a bullet-scarred wall, run your fingers along the edges of the damage (where permitted), and you encounter something that resists symbolic interpretation. The hole simply is - a fact of physics and history that no amount of narrative construction can entirely domesticate.

Ul. Łowicka; Ul. Fałata; Ul. Akacjowa.

The Tourist Gaze and Temporal Voyeurism

For me, the growing popularity of Warsaw as a tourist destination raises uncomfortable questions about the consumption of trauma. I fear Instagram feeds filled with carefully composed shots of bullet holes, accompanied by hashtags that flatten complex history into digestible content. The temporal bleeding then becomes a backdrop for selfies, the authentic traces of violence transformed into aesthetic objects.

This inevitable phenomenon reveals the postmodern condition at its most problematic: the transformation of everything, even trauma, into image and spectacle. The bullet holes, which once represented the rupture of normal life, become integrated into the smooth flow of tourist consumption.

Yet perhaps this integration is itself a form of temporal bleeding. The holes continue to disrupt, even when commodified. They resist the tourist gaze even as they attract it. Visitors come expecting picturesque decay but encounter something more unsettling: the persistence of violence in the urban landscape, the refusal of history to behave politely.

Ul. Fałata.

Photographing the Unphotographable

As a photographer working with these subjects, I'm acutely aware of the ethical complexities involved. How does one photograph a bullet hole without aestheticising violence? How can a camera capture temporal bleeding without flattening it into mere visual effect?

I've found that the most honest approach is often the most direct: straight documentation that doesn't try to beautify or dramatise. The holes speak for themselves. They don't need artistic interpretation to be powerful; they need only to be seen clearly.

Sometimes the most effective photographs are the most uncomfortable ones: images that refuse to resolve into pleasing compositions, that maintain the awkwardness and disruption that the holes themselves represent. A bullet hole partially obscured by a lamp post, its historical significance competing with mundane present-day life. A facade where preserved damage sits next to fresh renovation, the temporal bleeding made visible through stark contrast.

The Digital Afterlife of Analog Wounds

In our digital age, these analog wounds take on new meanings. Shared on social media, reproduced in articles and exhibitions, they enter a realm of infinite reproducibility. Each digital reproduction is a form of temporal displacement - the 1944 bullet hole viewed on a 2025 smartphone screen in any location worldwide.

This digital circulation creates its own form of temporal bleeding. The wounds become globally present, simultaneously local to Mokotów and universal to anyone with internet access. They exist in multiple temporal frameworks: as historical artefacts, as contemporary images, as viral content, as aesthetic objects.

The postmodern implications are staggering. These bullet holes, which represent the most local and specific of historical moments, become part of the global flow of images that characterises our hyperconnected age. They maintain their temporal specificity while participating in the timeless now of digital culture.

Resistance and Resilience

What strikes me most about Mokotów's bullet holes is their stubborn persistence. They have survived not only the original violence that created them but decades of urban development, political change, and social transformation. They represent a form of material resistance to the forward march of progress and forgetting.

In a world increasingly dominated by the virtual and the simulated, these holes insist on the relevance of the material and the real. They cannot be updated, patched, or upgraded. They can only be preserved or destroyed, maintained or erased.

This binary choice - preservation or erasure - cuts through postmodern ambiguity with surprising clarity. In a culture of endless interpretation and reinterpretation, the bullet holes demand decision. They force us to confront the question: What do we owe to the past? How much disruption of the present are we willing to accept in order to maintain historical truth?

Conclusion: Living with Wounds

The bullet holes of Mokotów teach us something crucial about temporality in the postmodern age. They show us that time is not simply a resource to be managed or a dimension to be manipulated, but a lived experience that can be wounded, interrupted, and forced to bleed across chronological boundaries.

As I continue this project, I'm struck by the way these holes insist on the ongoing presence of the past. They refuse the postmodern tendency to flatten all historical moments into equivalent "content." They maintain the specificity of their historical moment while radiating influence across decades.

Perhaps this is the ultimate lesson of temporal bleeding: that the past is not safely contained in history books or museums, but lives on in the material world, sometimes in ways that resist our attempts at control or interpretation. The bullet holes remind us that we share our present with the persistent traces of previous presents, that the city we inhabit is layered with the experiences of those who came before.

In photographing these wounds, I'm not just documenting war damage - I'm trying to capture something more elusive and more important: the way the past refuses to stay past, the way trauma persists in brick and mortar, the way a city's skin bears permanent marks of its history.

The holes bleed time, and in their bleeding, they keep alive something essential about human experience: that we are not just present-tense beings, but creatures haunted and sustained by the persistence of what came before. In Mokotów's bullet-scarred walls, the past doesn't just speak - it screams, and its voice carries across the decades with undiminished force.