I have less than two weeks left in Belgrade and apparently I should be panicking. You see, I haven't done the things. I haven't watched the sunset from Kalemegdan Fortress. I haven't taken the atmospheric riverside walk along the Danube at golden hour. I haven't whiled away a perfect afternoon in one of those picturesque cafés that show up in every "Beautiful Belgrade" video YouTube keeps suggesting I watch.

And when I caught myself thinking I better... something stopped me. I don't want to. I already have my Belgrade.

This realisation has arrived in fragments over the last few days, vaguely watching those curated travel videos that insist on appearing in my You Tube recommendations. They all follow the same script: here are the perfect experiences, the prescribed moments, the things you must do to say you've properly experienced this city. View sunset from fortress. Stroll along river. Sip coffee in charming courtyard.

My Belgrade. Autumn 2025.

But here's what bothers me about this formula - and what my new best mate Viktor helps me articulate: these prescribed experiences don't necessarily deliver meaning. They promise it, certainly. They're packaged and presented as meaningful.

But meaning doesn't work through prescription. It can't be manufactured through a checklist of curated moments.

The thing is, Frankl's entire therapeutic framework rests on a simple but radical premise: meaning cannot be given, only found. It emerges not from what we seek but from how we respond to what seeks us. Life presents situations, and meaning is discovered in our response to those situations - not in engineering circumstances designed to feel meaningful. This is why his approach is called logotherapy rather than, say, "meaning creation therapy." The logos (pronounced (LOH-gos, not LOG-os) - from the Greek for "meaning" or "reason" - is already there, waiting to be discovered through authentic encounter with the world as it actually is, not as we wish it to be or as algorithms suggest it should be.

The curated travel experience inverts this entirely. It begins with the assumption that meaning can be prescribed, that certain activities at certain times in certain lighting conditions will deliver the desired emotional payload. Watch sunset at fortress equals meaningful experience. Stroll along river equals connection to place. It's a transactional logic, a kind of spiritual capitalism where meaning becomes something you purchase through correctly performed experiences. But Viktor spent years in Nazi concentration camps learning that meaning doesn't work this way. He watched people find profound meaning in the most horrific circumstances imaginable, not through choosing their situation but through how they responded to unchosen reality. And he watched others collapse in situations that should have been comparatively tolerable because they'd lost the ability to find meaning in anything that didn't match their expectations.

Anyway, my Belgrade isn't the one in those aforementioned videos. It's the one I encountered waiting for bus 78 in the rain, watching an old man argue with the driver about whether his monthly pass was still valid. It's the garbage truck that wakes me at 5am every Tuesday and Thursday, its hydraulic whine echoing between the apartment blocks, and my slow adjustment to this rhythm until I started waking naturally just before it arrived, my body learning the city's schedule.

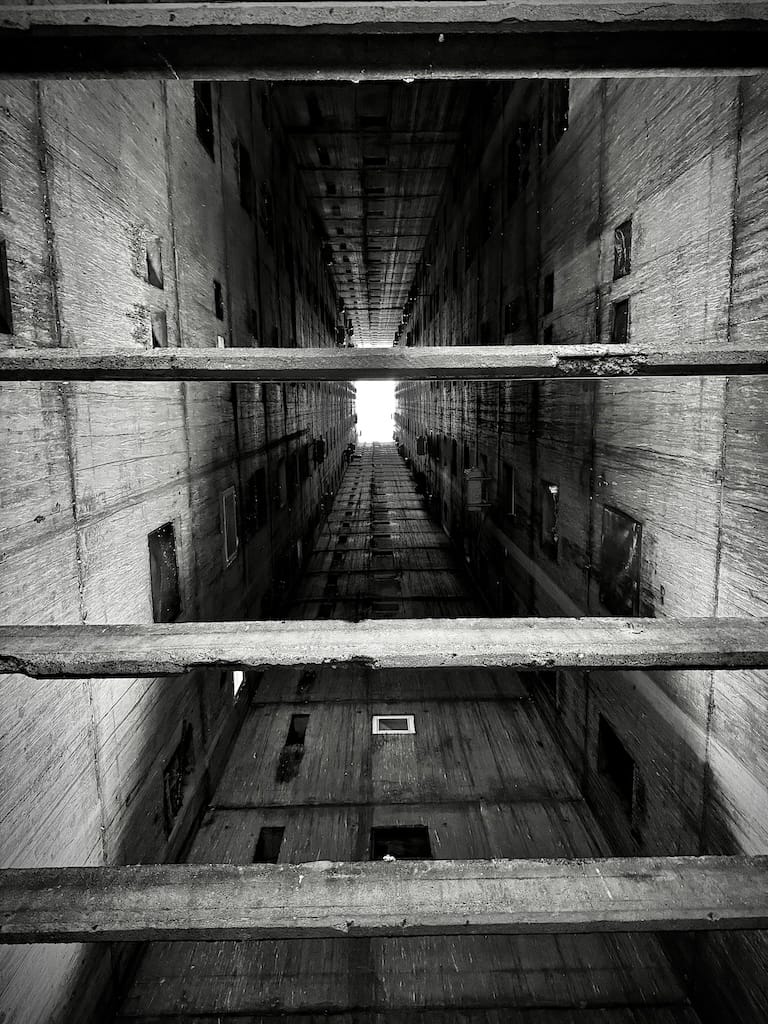

A city of contrasts.

It's being kicked off a tram at Slavija because the driver decided, for reasons never explained, that this was the end of the line, and standing there with a dozen other confused passengers as the empty tram pulled away. It's walking home from Maxi with heavy shopping bags as snow begins to fall, the streets emptying, the city becoming quiet and mine. It's the particular quality of light at 4pm in December when the sun is already setting and the street lamps come on and everything takes on this amber stillness.

These aren't Instagram moments. They're not even particularly interesting to describe. But they're real in a way the curated experiences can never be, because I didn't choose them - I responded to them. They happened to me rather than being staged by me. And in that distinction lies everything.

This is where my other pal, Jean Baudrillard becomes useful, because what those "Beautiful Belgrade" videos present isn't Belgrade at all - they're a simulation of Belgrade, optimised for visual consumption and social media validation. The map replacing the territory. The curated experience becoming more "real" than actual experience. Baudrillard's concept of hyperreality describes exactly this phenomenon: the proliferation of signs and simulations to the point where they become more real than the reality they supposedly represent.

The simulation doesn't just mediate reality - it replaces it, becomes the reference point against which actual experience is measured and inevitably found wanting.

Think about what happens when you visit a famous landmark. You're not really seeing the landmark - you're seeing your memory of photographs of the landmark, and you're simultaneously imagining the photograph you're about to take of the landmark. The actual thing in front of you becomes almost invisible, sandwiched between its simulation-past and simulation-future. You're performing an encounter with something you've already encountered countless times through images, and the performance is primarily oriented toward producing new images that will allow others to perform the same simulation, right? It's copies all the way down, with no original anywhere in the chain.

This is hyperreality: when the simulation becomes the reference point, when we measure our lived experience against the mediated version and find ourselves wanting. When I catch myself thinking "I should watch the sunset from Kalemegdan" not because I want to, but because I'm supposed to want to - because the algorithm has told me this is what "experiencing Belgrade" looks like.

The thought isn't even mine. It's been inserted into my consciousness through repeated exposure to images of other people having the experience I'm now supposed to desire.

The paradox is that the more we chase these prescribed meaningful experiences, the further we get from actual meaning. We perform the sunset. We perform the riverside stroll. We perform the charming café afternoon. And in performing them, we're no longer in them. We're enacting a script written elsewhere, by someone else, for an imagined audience that exists primarily in our heads. The performance requires constant self-surveillance: Am I positioned correctly? Is the light right? Will this translate into the image I need? The present moment becomes instrumentalised, valuable only insofar as it can be converted into future proof of having been present.

Vik-E-Boy would call this the "will to meaning" gone wrong - seeking meaning in the wrong places, through the wrong mechanisms. Not through authentic encounter but through simulation. Not through response but through performance. He distinguished between the will to meaning (healthy, oriented toward discovery) and the will to pleasure or will to power (neurotic, oriented toward possession and control). The curated travel experience belongs firmly in the latter category. It's about possessing the experience, extracting its value, demonstrating that you've acquired it. Meaning becomes another commodity to collect and display.

I didn't deliberately set out to avoid the tourist experiences. I just lived here. I established routines. I found my bakery, my grocery store, my quiet shortcuts. I learned which tram drivers are psycho and which aren't. I discovered that the small park near Tašmajdan is almost always empty at 9am and good for thinking. I figured out that on Thursday evenings the smell of roasting peppers drifts from the window of an apartment in Blok 32. These small competencies, these accumulated navigations - surely this is what makes a place yours? Not the sunset photos. Not the picturesque moments. The mundane mastery. The daily texture. The slow accumulation of encounters that build into something like belonging.

Belgrade Autumn 2025

And here's what I've come to realise: I don't need to perform my departure. There's a cultural script that says when you're leaving a place, you're supposed to frantically tick boxes, squeeze in the experiences you missed, take the photos that prove you were properly there. It's a kind of mild panic - the fear that if you didn't do the prescribed things, your time doesn't count. That you failed to properly extract the experience. That you'll leave with nothing to show for it. But that script serves the simulation, not the person living it.

It assumes that experience only becomes real when converted into image, that time only counts when documented according to established visual grammar.

This isn't the first time I've refused this script. When I left Warsaw after three months, I hadn't set foot in the Old Town once. Not once. Now, I'd been there before on previous visits, but it just isn't my Warsaw. My Warsaw is the 108-kilometre circular route I walked repeatedly, the residential neighbourhoods nobody photographs, the communist-era estates that don't appear in any guidebook. When my brother Ian came to visit, I took him to the Old Town because that's what you do - you show visitors the postcard version, the simulation they've already seen. But mostly we walked around the suburbs, the residential neighbourhoods, the places I'd come to know through daily living. When he left, he told me the only thing he wouldn't bother with "next time" was the Old Town. The curated bit. The part that's supposed to matter turned out to be the most disposable part of the experience.

He'd found his own Warsaw through walking with me, through encountering the city as lived space rather than as image-to-be-consumed.

So, my Belgrade is already complete.

It's in my muscle memory - the exact pressure needed to open the stubborn door to my apartment, the timing of the pedestrian crossing at Vukov Spomenik, the sound of Serbian spoken in the pharmacy when I'm trying to buy ibuprofen with my terrible Serbian and elaborate hand gestures. It's in my body, my routines, my small daily negotiations with this place. That's not curated. It's not optimised for sharing. But it's mine in a way a sunset photo could never be. It exists in the private accumulation of moments that can't be translated into image or narrative without losing what made them matter in the first place.

I think what those travel videos are really selling is the fantasy that meaning can be captured - that if you position yourself correctly, at the right time, in the right light, you can possess the essence of a place. You can take it with you. Package it. Own it. But meaning doesn't work like that. It's not in the place. It's in the relationship between you and the place, in the accumulated moments of encounter and response. And you can't photograph that. You can't package it. You can only live it, and in living it, let it become part of how you understand yourself and the world.

So no, I won't be watching the sunset from Kalemegdan before I leave. I'll be walking home in the dark from buying groceries. I'll be waiting for the bus. I'll be living the last two weeks the same way I lived the ten weeks - paying attention to what actually happens, rather than staging what's supposed to. Not because I'm superior to those who do chase the curated experiences, but because I've learned that meaning, for me at least, lies elsewhere. In the mundane. In the unperformed. In the moments that happen when I'm not trying to make anything happen at all.

That's my Belgrade. And that's enough.